During pregnancy, the breasts expand, the resting heart rate speeds up, and organs change to accommodate the growing fetus. And now, scientists have added one more thing to this list: the gut grows dramatically.

According to new research conducted in mice and 3D models of human tissue, the inside lining of the small intestine — known as the epithelium — changes its composition and doubles in size during pregnancy, as well as during breastfeeding.

During these critical stages of reproduction, mothers have to eat more nutrients to support their baby’s growth and development. The team behind the new research speculates that these gut changes may enable mothers to absorb more nutrients from the food they eat and thus be even more responsive to their babies. However, this idea has yet to be confirmed.

“Our team has discovered an amazing new way of understanding how a mother’s body changes to keep babies healthy,” study co-author Josef Penninger, scientific director of the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Germany, said in a statement. The team made the discovery after studying the role of a signaling molecule called RANK, which can be found in many tissues around the body. This molecule has previously been shown to control the formation of milk-producing mammary glands in the breasts. Hormones involved in reproduction, such as progesterone, also increase RANK production within these glands, suggesting that the molecule helps orchestrate the body changes associated with pregnancy.

Beyond breast tissue, RANK is also found in the intestinal epithelium — but until now, little was known about its role.

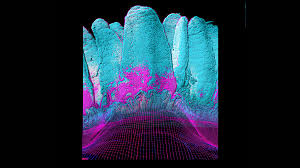

In the new study, Penninger and his colleagues used stem cells to grow tiny, 3D replicas of the human and rat small intestine. They grew these “organoids” with the help of special chemicals. They then exposed cells within the small-intestine to RANK, which caused several structural changes.

Namely, the tiny, finger-like protrusions that protrude from the epithelial cells suddenly lengthened and flattened. These projections, known as villi, help increase the surface area of the intestine, thereby increasing the absorption of nutrients through the tissues.

The team found that the same happened in pregnant and lactating mice. However, without RANK, these changes did not occur. In separate experiments in which they genetically modified mice not to produce RANK, the intestines remained the same.

Furthermore, the milk produced by lactating mice contained fewer nutrients than that produced by mice lacking RANK, and the former mice gave birth to comparatively lower-weight babies.

The team theorized that these findings, taken together, suggest that the intestinal epithelium is rebuilt during reproduction to maximize nutrient absorption for the developing baby.

“These new studies provide for the first time a molecular and structural explanation of how and why the intestine changes to adapt to mothers’ increased nutrient demands,” Penninger said.

Moving forward, the team plans to investigate whether this tissue remodeling also occurs in humans, as well as to explore whether factors other than RANK also regulate this process.